Inherited and acquired thrombophilia’s also referred to as hypercoagulable conditions, may contribute to an individual’s risk for VTE. While the majority of patients with VTE will have a combination of transient and continuing risk factors that result in VTE, the minority will have a detectable underlying hypercoagulable state. However, identification of these patients can have important implications for risk of recurrence, intensity and duration of anticoagulation, and family members’ risk for thrombosis.

Inherited Thrombophilia’s

Inherited thrombophilia’s should be suspected in patients who have a VTE at a young age, multiple family members with VTE, VTE in unusual locations, idiopathic or recurrent VTE, or a history of recurrent miscarriages. The prevalence of specific inherited thrombophilia’s varies according to the population of interest. In the general population, inherited thrombophilia’s are infrequent compared with “traditional” VTE risk factors, such as cancer, immobility, surgery, trauma, and obesity. However, in patients who have experienced an initial episode of VTE or have a family history of VTE, the prevalence of inherited thrombophilia is increased.

Thrombophilia testing is typically performed to assess the risk of recurrent VTE in a patient with an initial or multiple events. Importantly, however, only a subset of inherited thrombophilia’s significantly increase the risk of VTE recurrence. While deficiencies of protein C, protein S, or antithrombin consistently increase the risk of recurrent VTE, more common inherited thrombophilia’s such as factor V Leiden and the prothrombin gene mutation have not been shown to increase the risk of recurrence. In an observational study evaluating the impact of factor V Leiden and the prothrombin gene mutation on VTE recurrence, neither heterozygosis, compound heterozygosis, nor patients homozygous for either factor V Leiden or the prothrombin gene mutation was associated with VTE recurrence.

Acquired Hypercoagulable States

Antiphospholipid antibodies comprise the major acquired hypercoagulable states and are potent acquired risk factors for both venous and arterial thromboembolism. Although hyperhomocysteinemia may result from inherited mutations in the gene encoding methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), it is most commonly acquired due to dietary deficiency in folic acid.

Thrombophilia Evaluation

The evaluation for thrombophilia or a hypercoagulable state is most helpful when results will assist in decision-making for prevention or treatment of VTE or otherwise influence the care of the patient and his/hers family members. The main rationale for performing thrombophilia evaluations includes selecting the optimal agent and duration of anticoagulation, predicting the risk of VTE recurrence, determining the optimal intensity of thromboprophylaxis, assessing VTE risk with pregnancy or hormonal contraceptive or replacement therapy and identifying family members at risk for thrombosis. Patients seeking an explanation for an arterial or venous thrombosis, especially if unprovoked, unexpected, or in the absence of risk factors, will often also request thrombophilia testing.

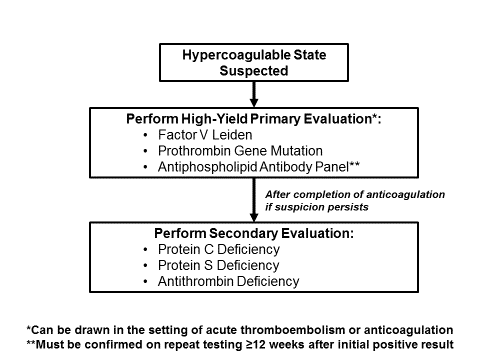

A stepwise strategy for thrombophilia testing that considers the clinical scenario (when to test), the implications of testing (why to test), and then the overall approach to testing (how to test) is often the most fruitful (Figure 3). A selective strategy begins with an initial thrombophilia evaluation focused on the highest yield testing, factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin gene mutation, and antiphospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-prothrombin antibodies, and anti-β2 glycoprotein-1 antibodies). Although antiphospholipid antibodies require confirmation at least 12 weeks after an initial positive result, polymorphisms detected on genetic testing for factor V Leiden or prothrombin gene mutation represent true positives, regardless of when the testing is performed. A secondary evaluation for less frequent thrombophilia’s, such as deficiencies of protein C, protein S, and antithrombin, may be performed after completion of anticoagulation if a high index of suspicion for thrombophilia exists and the initial laboratory panel is negative. Because low levels of protein C, protein S, and antithrombin may be observed in the setting of acute thrombosis and anticoagulation and do not necessarily indicate true thrombophilia, testing for these thrombophilia’s should be deferred in the acute setting. Increased levels of protein C, protein S, and antithrombin do not represent a disease state. Additionally, it is vital to understand the possibility of false positive or abnormal test results of certain thrombophilia’s in the setting of an acute thrombosis, or during use of DOAC’s, warfarin or heparin, or LMWH which are noted in (Table 7). Testing for thrombophilia’s should be delayed at least 48 hours for the patient on DOAC’s and 2 weeks for those on warfarin. (Table 8) provides tips for testing the patient with a suspected thrombophilia.

Although the desire to perform thrombophilia testing during the patient’s emergency room or urgent care visit or acute hospitalization for VTE is frequently high, a strong case can often be made to defer evaluation to a follow-up clinic visit when there is more time to discuss the implications and when the patient may be more emotionally and psychologically prepared.